Just west of midtown Tulsa, three 1940s-era sand levees stand between the Arkansas River and hundreds of acres of refining and chemical hazards. The Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee System failed inspection in 2007. After Tulsa narrowly escaped disastrous flooding in 2019, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers quietly sealed the fate of the levees with a rushed feasibility study.

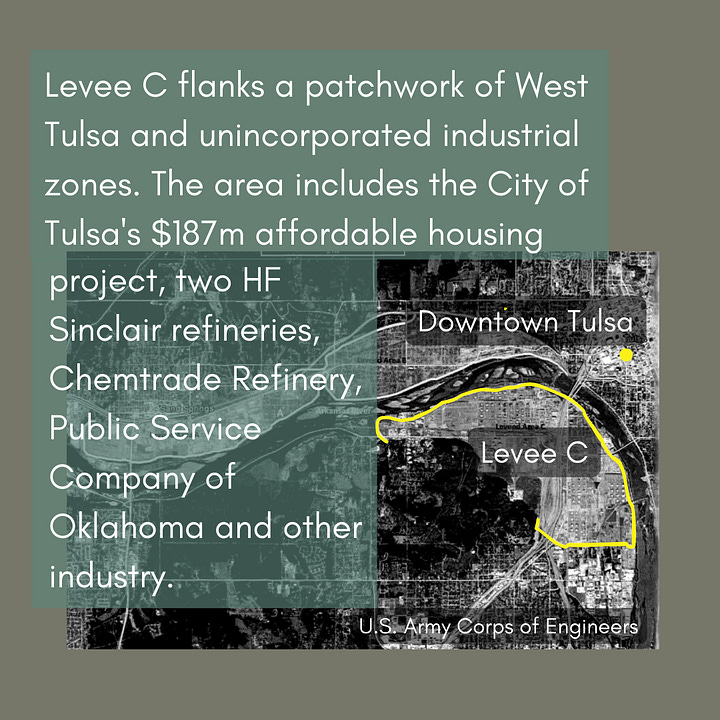

The Corps elected not to repair Levee C, which surrounds the HF Sinclair1 refineries and other industry, and not to raise Levees A and B beyond their 80-year-old design height.2

A compounding threat looms upstream. Like other outdated infrastructure, Keystone Dam is ill-equipped for a future of increasingly extreme weather events. In the Corps’ worst-case flood scenario, the dam overtops by up to 12 feet, unleashing a wave of destruction downstream.3 Floods of a much lesser magnitude, which are far more likely, would also be catastrophic.

Tulsa’s busted levees are buying time for an area with an estimated $2 billion in infrastructure and up to 15,000 people.4 Downstream through Tulsa County, in Brookside, Bixby and beyond, thousands more residents inhabit an unprotected floodplain overrun with development.5 All are at risk of environmental and public health disasters from flooding.

According to Tulsa’s All Hazard Mitigation Plan, residents have low awareness of the potential for “devastating danger and damage” due to flooding. A powerful public narrative of exceptionalism compounds this deficiency. In a 2021 Facebook post, Mayor G.T. Bynum called Tulsa “one of the two best cities in America for flood protection!”

Officially, it’s true: The National Flood Insurance Program recognized Tulsa’s achievements in floodplain management with a Class 1 rating in 2021.6 But the city’s efforts have largely focused on local creeks. Floodplain manager Ron Flanagan said elected officials hide behind the rating system to mask Tulsa’s overwhelming exposure to the Arkansas River.

Recognized nationally for his leadership in planning and hazard mitigation, Flanagan worked with the city for more than 50 years until his retirement in 2021.7 He said development in the Arkansas River floodplain has created a problem so big, the City of Tulsa does not address it.

“It’s the item that the City of Tulsa has swept under the carpet,” Flanagan said. “The people who know about it know better than to say anything about it.”

Flanagan said the specter of “political consequences” for speaking out about the river feeds the dysfunction.

“Especially for a community that is touted now as being the number one program in the entire nation,” Flanagan said. “They don’t want to talk about the existing vulnerabilities, and our inability to address those problems like we addressed all the interior small creek problems. The Arkansas River is too hot and too big to handle. And you’re not gonna get any straight answers.”

“It’s the item that the City of Tulsa has swept under the carpet,” Flanagan said. “The people who know about it know better than to say anything about it.”

Since the levees failed inspection in 2007, the City of Tulsa has championed more than half a billion dollars in cosmetic river development at one location. The centerpiece is Gathering Place, a $465 million park donated to Tulsa’s River Parks Authority by the George Kaiser Family Foundation in 2014.8 Adjoining the park, the new Zink Dam and “Williams Crossing” bridge are expected to open in the Fall of 2024.

TIME named Gathering Place, opposite Levee C, one of the 100 World’s Greatest Places in August 2019.9 The following month, the Corps’ draft feasibility study painted the park as an obstacle to raising the height of the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee System.10 Elected officials encouraged the public to read the draft but shared no reservations about it.1112

In an interview, Levee Commissioner Todd Kilpatrick described his reaction to learning that the Corps had excluded Levee C from the planned repairs:

“This sucks,” Kilpatrick said. “What the hell are we even doing here?”

Publicly, however, he called it “a great plan.” Kilpatrick qualified this statement in a recent interview, saying the partial repairs would be “a hell of a lot better” than no repairs at all. Given Tulsa’s Arkansas River flood probabilities, the condition of the floodplain, and the status of the levees and Keystone Dam, this is debatable.13

The Corps released the final levee report as a pandemic shut down the world in March 2020. In January 2022, Bynum heralded $137.4 million in federal funding for the levee repairs as “tremendous news.”

“Our levee system will be fully functional and help protect our community from potential flooding for generations to come,” the mayor announced in a Facebook post.14

“We got our money,” County Commissioner Karen Keith said excitedly at a press conference.

“This has been a priority of mine for as long as I can remember,” wrote then-Sen. Jim Inhofe, who voted against the funding.15 Inhofe said the repairs would “protect our children and our children’s children.”

At the time, Kilpatrick said the funds “made sure Tulsans are safe from floods for many years into the future.” Months later, he cast doubt that the repairs will occur due to rising costs and the 35 percent local cost share.16 He said the project today would run $180 million to $200 million.

“How are you gonna come up with that money?” Kilpatrick said. “For some of these local officials to celebrate—they don’t know.”

“We have no idea what the interest rate for that is,” Kilpatrick continued. “The knowns are the unknowns for us right now.”

Keith confirmed in an August 2022 interview that “we’re probably going to need more money” but did not provide a timeline for securing it.

“This sucks,” Kilpatrick said. “What the hell are we even doing here?”

Most Tulsans with whom I discussed this series had no meaningful knowledge of the planned levee repairs. As of April 2023, this included the mayor.

Bynum told me he relied on Kilpatrick, Keith, and City Engineer Paul Zachary to read the levee study in its entirety.

“Are you aware that we’re not repairing Levee C,” I asked, “and we’re not raising the height of the levees beyond their 80-year-old design height?”

“I don’t know,” Bynum replied.

“You don’t know,” I said.

“No,” Bynum said. “I don’t know which—what you’re talking about.”

“Okay,” I offered, “so we have three levees, A, B and C—”

Bynum turned to another person in line:

“You have been waiting—” he said.

“This is more of the same though, by the way,” Bynum said, turning back to me. “You’re arguing with me.”

A few months prior to his retirement from River Parks Authority, Executive Director Matt Meyer also did not know what was happening with the levees.

“No, I mean I don’t know that it impacts River Parks,” Meyer said. “Maybe it does and I don’t know it.”

The same was true of Jeff Edwards, the former director of Sand Springs Parks and Recreation who succeeded Meyer in October 2022.17

Many of Keith’s constituents live near the river or behind the levees. Are they aware that Levee C is not included in the planned repairs?

“You know, I’m not sure about that,” Keith said, matter-of-factly.

“That concerns me,” I replied. “The impression you all have sent is not what is actually happening.”

“Okay,” Keith said. “Yeah. We can, we can—uh, maybe get that message out. I’ll have Todd [Kilpatrick] work on what needs to be said with the Corps, and we can, uh—bolster that.”

Keith stopped replying to my messages after our interview. Ten months later, Kilpatrick said Keith had not contacted him about this issue.18

Joe Kralicek, executive director of Tulsa Area Emergency Management Agency, questioned the need to “panic the public into believing that the levee system is not going to function.”

“I understand what you’re saying, that there’s a little bit of exaggeration going on—possibly,” Kralicek said. “Do I feel that it is important for the public to understand the actions that their government is taking? Yes. Now, it is up to the public to also keep track. … I work at the pleasure of my elected officials. So I am not going to disagree publicly with what they say.”

The hair-raising lessons of other flood-prone communities betray the magnitude of Tulsa’s problems along the river.

After Hurricane Katrina drowned coastal Louisiana and Mississippi beneath a 28-foot storm surge, the federal government spent $14 billion repairing floodwalls and levees around New Orleans to the 100-year flood standard.19

In 2019, less than a year after the New Orleans project’s unofficial completion, the Corps announced that the system “will no longer provide [a 100-year] level of risk reduction as early as 2023” due to sea level rise and sinking levees.

As south Texas struggles to recover from multiple historic flood events, residents could wait another two decades for a $34 billion coastal fortification plan to be fully funded and executed. 20

As the Corps acknowledged, Levee C will “continue to degrade.”21 Kilpatrick said the partial repairs to Levees A and B could take a decade or more if they occur: two to five years for engineering and design, and a minimum of five for construction.

If the levees make it that long, the project will leave Tulsans with an inadequate system built for the past and a dangerous floodplain with worsening odds.

3—Still Fighting It

Tulsa has fought the Arkansas River for more than a century. Despite decades of frequent flooding, the city allowed the floodplain to be developed as if the river could be …

If you’re new to Watershed, start at the beginning.

Support independent investigative journalism.

Watershed is the result of thousands of hours of reporting, writing, editing and fact-checking, with no institutional funding or outside sponsorship. If you have the means, help us deliver essential reporting to everyone who needs access:

Subscribe for $7/month or $64/year.

Make a sustaining contribution at a higher level of your choice (choose Critical Mass and enter any amount above $64).

Purchase a gift or group subscription.

All free and paid subscribers will receive dispatches a few times per month: one or more full-on articles, plus updates and bonus content arriving more frequently. When the series winds down, I’ll let you know where I’m headed next. You can modify your subscription or cancel any time by logging in to your account. Thank you for your interest.

Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides pro bono legal counsel for this series. You can support their work here.

Formerly HollyFrontier

For details about the Corps’ decision, see p. 101 of the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee Feasibility Study (Final) and p. 93-94 of the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee Feasibility Study Draft Report.

Not all of the repairs recommended in the levee study will occur. As of August 4, 2023, the following repairs were still in the plan:

1. Filtered berms and new toe drains on the landside of Levees A and B

2. Landside reinforcement at the low point of Levee B to buy time before failure in an overtopping event

3. Filters on the Charles Page Floodway structure. (This repair is complete.)

4. Repair or abandonment of selected conduit through Levees A and B

A filtered berm on the landside of the Levee B tieback was also under consideration, but Levee Commissioner Todd Kilpatrick said it could be eliminated after further study. The same was true of a cutoff wall on the waterside of Levee A, which the Corps recommended constructing to try and mitigate contaminated seepage from Sand Springs Petrochemical Complex Superfund site. Recommended detention ponds near the Levee B tieback were eliminated.

The Corps excluded pump stations along Levee C (in addition to the levee itself) from the planned repairs. However, due to damage from the 2019 flood, federal funds from two other sources are being used to update the pump stations along all three levees, according to Kilpatrick. Pump stations return seepage to the river and transport stormwater, which cannot reach the river when outfall gates are closed during high water events.

I will describe the levee study in greater detail in an upcoming article.

UPDATE—In March 2024, the Corps released a proposal to raise Keystone Dam by about 10.5 feet to store additional water during extreme flood events where the gates are fully open and the water continues to rise. Announced in the Keystone Dam Safety Modification Study, the plan also includes reinforcing the stilling basin below the dam to protect the spillway foundation from erosion.

David Williams, chief hydrologist for the Corps’ Tulsa District, said the modification would allow the reservoir to hold the estimated Probable Maximum Flood inflow of 1.67 million cubic feet per second (cfs) without overtopping while about 1 million cfs passes through the gates.

(The Corps currently estimates that Keystone Dam can release up to 989,000 cfs without overtopping; a higher reservoir means more pressure behind the gates and a slightly higher release during events like the Probable Maximum Flood.)

Williams said in an Aug. 6, 2024 email that congressional priorities and other factors will determine whether the Corps ultimately moves forward with the proposal.

“At this time it is reasonable to state that a recommendation has been made but additional steps are required before it moves into detailed design and construction,” he said.

Williams said the project has not progressed to the point of a detailed cost estimate but “will likely be in excess of $1B.” If the modification occurs, he estimated 5-7 years for detailed design and 10 years for construction, putting the theoretical timeline for completion in “the early 2040s (at the earliest).”

For details about the Probable Maximum Flood and maps of the inundation zone, read “Wall of Water,” the sixth article in this series.

For more information about Keystone Dam and Tulsa’s Arkansas River flood probabilities, check out “Still Fighting It” and “The Pool of Record.”

Source: Levee Commissioner Todd Kilpatrick

The city of Jenks, in southwest Tulsa County, also has a 1940s-era levee.

Tulsa shares the Class 1 designation with the Sacramento suburb of Roseville, California.

Hazard mitigation advocate and writer Ann Patton described Flanagan as “a visionary planning consultant who dedicated his life to stopping Tulsa floods.” In 2022, the Association of State Floodplain Managers recognized Flanagan with a lifetime achievement award for “unbridled passion, tenacity and guts” as a national leader in hazard mitigation. Flanagan received a Bronze Star Medal with Valor for his service in Vietnam.

Gathering Place is the largest private gift to a public park in U.S. history. The cost of the park involved $200 million from the George Kaiser Family Foundation, $200 million from businesses and private donors, and $65 million from the City of Tulsa.

In 2022, Gathering Place was one of seven public spaces across the U.S. admitted to the Partnership Lab at Central Park Conservancy’s Institute for Urban Parks. A press release for the program described Gathering Place’s intention to “revise their community engagement model” and create “a community-led vision for the park by building authentic, relevant relationships with stakeholders.”

See p. 93-94 of the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee Feasibility Study Draft Report.

Then-Sen. Jim Inhofe expressed confidence in the proposed repairs in a press release at the time.

Comments from just two private residents appear in the study’s Public Involvement appendix. Both express concerns that the Corps did not adequately account for potential releases of refining and chemical hazards if the levee system fails. Professional engineers Charles Pratt and Fred Storer, who submitted the comments, have followed Arkansas River issues closely for years and will appear in future articles.

Upcoming articles will address each of these considerations.

April 25, 2023, I asked Bynum whether he thought this statement was an accurate characterization of what’s happening with the levees. Bynum said it is “exactly what the levee commissioner has told me, based on the federal funding that Sen. Inhofe secured.”

The funding comes from Public Law 117-43 (see also H.R. 5305). Inhofe was unreachable for comment.

Local communities must repay 35 percent of the cost, amortized over 30 years. Kilpatrick secured $10 million for the levees from the 2016 tax package that greenlit the new Zink Dam. Tulsa also allocated $3.4 million in Improve Our Tulsa funds. These funds will go toward Tulsa’s share in the eventual repayment.

“I couldn’t tell you, honestly,” Edwards said in his first week as executive director of River Parks Authority. “I don’t know.”

UPDATE—Keith announced her candidacy for Tulsa mayor August 13, 2023. In an article that day, Tulsa World described the levee funding as one of Keith’s “biggest and most celebrated achievements as county commissioner.”

“We never could have fixed the levees without working across partisan lines,” Keith said. “I mean, Sen. (Jim) Inhofe collaborated with me from Day 1.”

The so-called 100-year flood estimate signifies a 1% chance that a flood of an estimated magnitude will occur in any year. I will explain Tulsa’s Arkansas River flood probabilities in an upcoming article.

(To say nothing of the plan itself; I have not analyzed it.)

David Williams, chief hydrologist with the Corps’ Tulsa District, confirmed this characterization of Levee C. For details, see p. 54 of the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee Feasibility Study (Final), which describes the condition of the levees and their future without repairs (called the FWOP, or Future Without Project).

Thank you for your hard work on this project and bringing these critical issues forward. It is very disturbing that problems of this magnitude have been ignored by City leaders, the people we trust to keep us safe. The devil is in the details, and you have done an excellent job of researching them and explaining them to the public. Looking forward to your next report!

This has been a concern of mine for years, and I used to live near the river, which I would not do for that reason anymore. Great work on your part … Thank you.