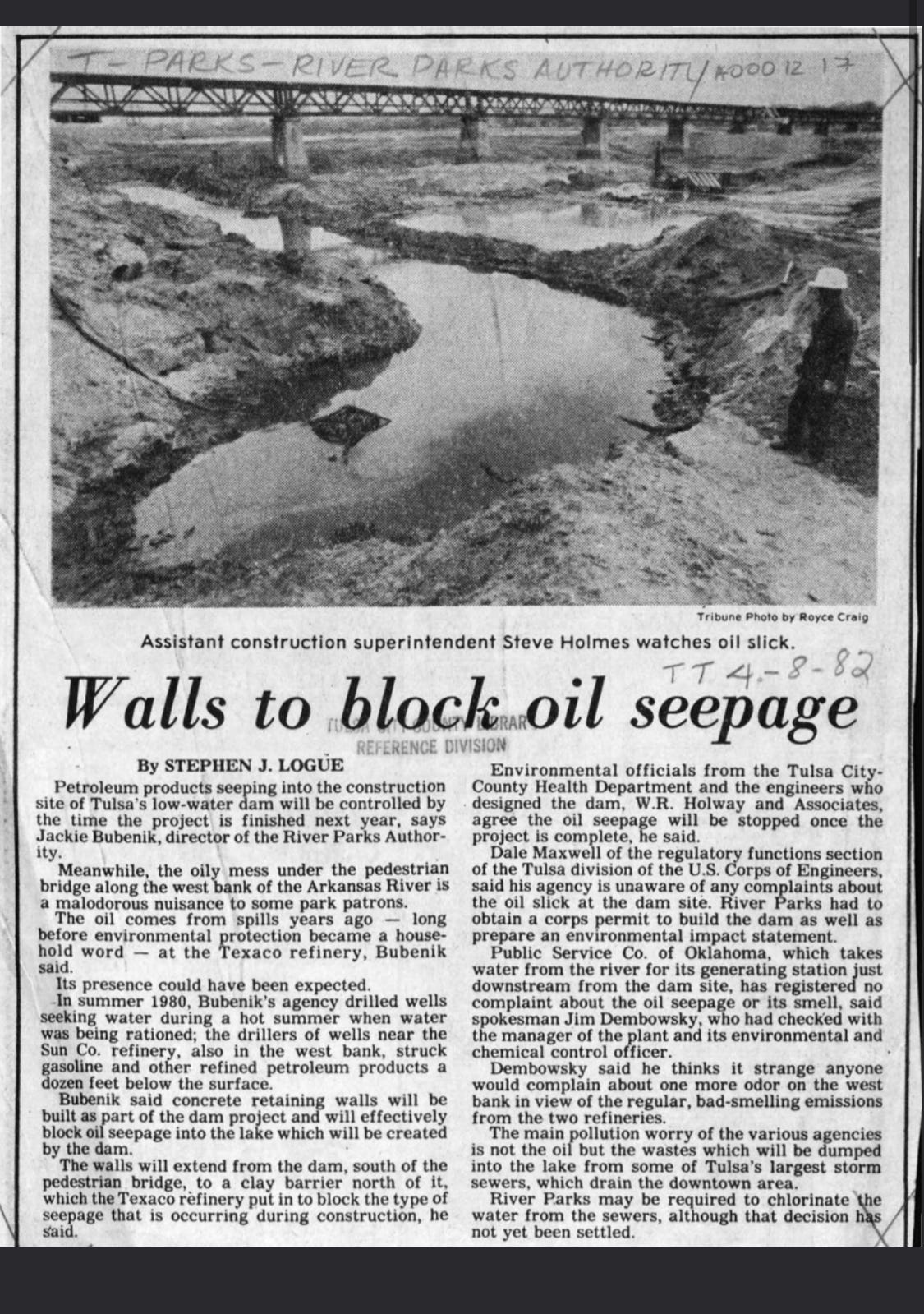

Downtown Tulsa, seen from the south, beyond the 23rd Street Bridge. Faintly visible in the middle distance, the east half of the original pedestrian bridge sits partially demolished next to the west construction cofferdam for the new Zink Dam and Williams Crossing bridge. Public Service Company of Oklahoma (PSO) is partially visible in the Arkansas River floodplain at left. Video courtesy of Fieldguide Media

Although HF Sinclair’s remediation projects at the riverfront refineries continue, the shadow of industrial contamination will loom over Zink Lake for the foreseeable future.

Public statements by officials involved with Zink Lake suggest they do not understand the problem.

In a Jan. 25, 2023 email to colleagues, Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum said HF Sinclair’s containment cap1 along Zink Lake “will prevent any chemical seepage.”

The following month, Bynum told the Brookside Neighborhood Association that HF Sinclair “assured him” the barrier would allow “no seepage.”

These statements are misleading. The caps contain a clay barrier wall designed to block oil, which floats on the groundwater.

However, they do not prevent chemicals and heavy metals dissolved in the groundwater—contaminants like benzene, napthalene and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)—from entering the river.

I verified my understanding with Fred Storer, a chemical and environmental engineer with more than 55 years of experience.

“If he said ‘will prevent any chemical seepage’ he is wrong,” Storer said in an Aug. 27, 2024 email. “The containment caps are oil-water separators; they retain the oil for recovery and let the groundwater pass to the river. Anything dissolved in the groundwater goes to the river including metals. …

“The containment caps were installed to keep oil from showing up in the river, that is all.”

After reading that lead and mercury are not normally water-soluble in their pure forms, I double-checked with Storer.

Could lead and mercury compounds end up in Zink Lake?

“Molly, I would be shocked if they were not found!” Storer replied. “Lead in the form of tetraethyl lead was used to increase the octane of gasoline until the early ‘70s. If leaded gasoline were spilled, it could find its way to the groundwater. Tetraethyl lead was shipped by rail and stored for gasoline blending. Sludge accumulated in TEL storage tanks and from time to time needed to be disposed of.

“Mercury was used in instruments, and significant quantities were disposed of.”

Storer called my attention to part of a 2021 report on the HF Sinclair East refinery by TRC Environmental Corporation and Hull & Associates.

The excerpt sheds new light on industrial hazards found near the RPA Leased Area.

Solid Waste Management Unit H (pronounced Shmoo-H), a landfill for historical refinery waste, is just over the fence from the leased area:

Former Waste Disposal Site SWMU-H was identified in May 2008 when buried drums were discovered during Facility landscaping and grading.

An approximate 9.5-acre tract of land adjacent to the Arkansas River located between the east tank farm fence and the east property fence was slated for public access under the management of the RPA.

Prior to opening the area to the public, a patch of tar-like material and debris was reportedly encountered during landscaping activities. The waste materials were excavated to a depth of approximately 3 ft bgs [below ground surface].

Deteriorated drums, petroleum impacted soils, and potential asbestos-containing materials were reportedly identified during excavation activities.

A portion of SWMU-H was apparently used as a waste disposal site from 1951 to 1982 for a variety of waste material (e.g., asbestos, wood scraps, glass, scrap metal, dirt, bricks, coke, gunite, spent catalyst, residue materials, tank bottoms)."

“Anything Texaco did not want was buried,” Storer said. “Buried drums could contain anything, including tetraethyl lead and mercury. If a sampling well happens to penetrate a spot next to a buried drum, very high concentrations of bad stuff will be discovered.

“BTW, TRC does high quality work for the East Refinery.”

At a May 22, 2024 community meeting, Corporate Environmental Specialist Arsin Sahba said HF Sinclair’s containment caps were designed for “upwards of 300,000 cubic feet per second (cfs)”—marginally higher flows than Tulsa’s 2019 flood and less than a third of what Keystone Dam was designed to release.

However, Sahba expressed “high confidence [the caps] could handle a flood higher than 300,000.”

“Typically in engineering, the safety factor is honestly one-and-a-half or two times that,” Sahba said.

Technical documentation provided by DEQ does not appear to contradict these statements.2 However, the engineer who designed the caps, TRC’s John Rice, appeared unaware of Tulsa’s Arkansas River flood probabilities in an earlier meeting.

Sahba also speaks at the beginning and end of the conversation. I trimmed Sahba’s comments for brevity.

A few months after this conversation occurred, refinery Supervisor Brian Moore said there was “a bit of a confusion with our consultant and his numbers” at the previous meeting.

“We have researched and gone back and found where, right now, the cap itself is designed for 277 cfs,” Moore said at the Aug. 9, 2023 meeting. “Which far exceeds a hundred-year flood.”3

“Two hundred and seventy-seven thousand,” Sahba clarified. “And that's the riprap.”

“And that's the riprap,” Moore said. “And then the concrete matting over the top of it is 305,000 cfs. ... So, they're designed to a one-and-a-half-times protection and a two-times protection factor.

“A flood of 2019 comes down through there, that material is gonna stay in place. Now that’s barring, you know, a big old tree that’s been ripped out of the ground. … I mean that could be the same with the wind damage that we had just during the last storm. … We’re very confident that we're not gonna have any problems with either one of these in the future.”

Tulsa resident Barbara VanHanken, who asked about the caps’ flood protection standard at the August 2023 meeting, began to ask a follow-up question.

"If there was to be a failure," she said.

A moderator interrupted VanHanken to move on to the next question.

At the May 22, 2024 meeting, Sahba said HF Sinclair checked the shoreline of the East refinery and PSO weekly and had not seen a hydrocarbon sheen there since the caps’ completion.

However, Sahba said HF Sinclair does not test the Arkansas River.

Additionally, the West refinery property continues to release hydrocarbons into Zink Lake.

The corporation currently uses containment booms and disposable sorbent booms—long, tube-shaped floating barriers meant to limit sheens. Sahba said HF Sinclair is exploring other ways to address the sheens.4

I asked Paul Zachary, the city’s director of Engineering Services, about the RPA Leased Area at a town hall April 24, 2023.

[At the time, I was unaware of HF Sinclair’s earlier determination that the leased area was not up to recreational standards for toxic waste and industrial contamination. I had not seen the soil data from the leased area or heard about the 2018 surface soil remediation work.

I also did not know about the irrigation wells at River West Festival Park. (If you’re new to the series, go back to the previous article, “That’s a Lot of Lead.”)]

“Do you feel like the public is aware that when they’re walking and riding their bikes on this trail, that they are on refinery property, right where pollutants have been seen emerging from the earth?” I asked.

“I would think if somebody is next to an oil refinery,” Zachary said, “they’re gonna know that they’re—“

“Oh—really?” I said, surprised.

“Just like Conoco up in Ponca City,” Zachary said. “Absolutely.”

“Oh, okay—” I replied.

“But it’s not—” Zachary began, “there’s not a public health—concer—I mean—”

“Well, it is a public health concern,” I said. “If there’s a tarry seepage emerging from the soil, which has happened in recent years—”

“Which they are taking care of,” Zachary said.

“Right,” I said, “But if it’s happening at all, that’s a public health concern.”

Zachary continued to direct the conversation back to HF Sinclair’s containment caps.

“HollyFrontier has invested, and is continuing to—” he said. “I think, this one, did they say it’s 10 or 15 million that they’re spending on this?”

“But the reality is, we know it’s contaminated.” I said. “And it will be even with the containment wall. … It’s not just contained in a plume underground that no one will ever make contact with.”

“Right,” Zachary said.

“These substances travel,” I said. “And that’s one of the reasons why they’re very problematic and dangerous.”

“I am not aware of one injury, illness or sickness that’s happened ever since the original Zink Dam was done in 1980,” Zachary said. “You remember the kayak run that used to be over here [along the west bank]? That’s where we originally were. And we met with the secretary of—and it’s like, We don’t want a [hydrocarbon] sheen, we don’t want any of those things. So we moved [the flume project] actually to the east side of the river.”

“But you’ve built a recreational lake where there are known oil sheens, and known refinery contamination,” I said.

“That recreational lake has existed since 1980,” Zachary said.

“Well, but you tore out the dam and built a new one to build a new recreational lake,” I said.

“Right,” Zachary said. “And the nice thing about it is—”

“That’s not a rea—just because something existed since the ‘80s is not a reason to still be making that decision, right?” I asked.

“The nice—” Zachary continued.

“I mean, that’s not the basis for that, surely—is it?” I asked.

“The nice thing that what we have now is we are able to release—” Zachary paused, electing not to complete the thought.5 “If they have an issue, it’s with [Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality]. And the city, we want to know. We fully support this containment project.”

“We’re gonna do the water quality plan,” Zachary said. “Especially with who our neighbors are over here.”

“So are you planning to also test for refinery contamination?” I asked.

“No,” Zachary said. “They’re doing that.”

“They do not test the river,” I said.

“They don’t—I thought they did test the river as they have their issues,” Zachary said. “I think they did do some grab samples.”

“He said, ‘We do not test the river,” I replied, referring to Sahba.

“They don’t routinely,” Zachary said.

“He specifically said, ‘We do not test the river.’” I said. “I asked him.”

“Okay,” Zachary said. “On an ongoing basis.”

“He said ‘We do not test the river.’”

The City of Tulsa began sharing the results of nominal testing for refinery contamination in Zink Lake in January 2024.

The city tests for Cadmium, a highly toxic metal, and Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH), a general way to detect the presence of hydrocarbons found in crude oil.

Sampling occurs just once a month, with results taking a minimum of 4 to 5 days for Cadmium, and 10 to 14 days for TPH to be posted online.

Guy de Verges, a geologist and environmental consultant to industrial operators along the river since 1992, said on a July 24, 2024 phone call that the city’s testing is nowhere near adequate to develop a meaningful picture of water quality and industrial hazards.

De Verges said the notion that the city would be willing or able to conduct such an inquiry is unrealistic.

“The list of potential chemicals and problems is—it's a long list,” de Verges said. “And the cost of doing the analysis is probably not practical. So using Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons and bacteria is kind of like a canary in a coal mine. You might be able to catch some stuff, but you're certainly not gonna notice it all.

“And Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons also just kind of scrapes the surface of the kind of, you know, light-end contaminants that you might find in the river that are hard to collect and expensive.”

Finding and interpreting the city’s test results is another matter.

Before accessing the Zink Lake Water Quality dashboard, users must accept a series of terms and conditions, including:

The City makes no claims or guarantees about the accuracy or currency of the contents of this website and expressly disclaims liability for errors and omissions in its contents. …

All information and data on this website is subject to change without notice.

Neither the City nor its affiliates, employees or agents shall be liable for any loss or injury caused in whole or in part by use of this website or in reliance upon the information contained herein or linked hereto.

Behind the fourth and final tab of the dashboard, the ninth of 11 links takes you to a technical spreadsheet titled, Zink Lake Cadmium and TPH PDF.

The page says the city is testing for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons “in response to citizen feedback.”

There is no mention of the refineries anywhere on the site, even on interactive maps of the river and its surroundings.

12—A Strong Odor of Petroleum

Unsettling reports from Tulsa’s Big Dam Party began to trickle out before the weekend was over: a strangely casual account of two sisters and…

The City of Tulsa plans to open Zink Lake to the public this weekend—Aug. 30, 2024.

Watershed provides the public with critical information you won’t find anywhere else.

This series was created with no institutional funding or outside sponsorship. In other words, we could really use your support.

If you have the means, help us share essential reporting with everyone who needs access:

Subscribe for $7/month or $64/year.

Make a sustaining contribution at a higher level of your choice (choose Critical Mass and enter any amount above $64).

Purchase a gift or group subscription.

All free and paid subscribers get the latest updates delivered to your inbox, plus access to the full archive at mollybullock.substack.com. You can modify your subscription or cancel any time by logging in to your account.

Previously:

If you’re new to Watershed, start at the beginning:

1—The Natural Law

In the hills above Tenkiller reservoir, shrouded in forest on a blustery April morning, Casey Camp-Horinek (Ponca) addressed a circle of visitors. Camp-Horinek stood in a black and red hoodie, red ribbon skirt and traditional beadwork. Beneath swaying Blackjacks and Post Oaks, she opened Convening of the Four Winds, the second in a series of intertribal…

To reduce the amount of oil seeping into Zink Lake, HF Sinclair capped about 250 feet of shoreline below Zink Dam in 2022 and about 800 feet above it in 2024. The new concrete river banks are easy to spot if you’re looking from Gathering Place.

I asked Charles Pratt to help me understand whether permitting documentation provided by DEQ supports this claim. Pratt is an electrical engineer with decades of experience working on water control structures.

“Let's put it this way,” Pratt said in an Aug. 27, 2024 email. “I cannot disprove their claims. Nature will be the final judge.”

The Corps’ latest 100-year Arkansas River flood estimate for Tulsa is 270,000 cfs, signifying a 1% chance of near-2019 flooding occurring in any year. However, flood probabilities mask an important range of uncertainty, called a confidence interval.

The Corps reported 95% confidence that the so-called 100-year event would fall between 174,900 cfs and 417,000 cfs: a flood that would likely cause the Tulsa-West Tulsa Levee System to fail.

Sahba said HF Sinclair is also assessing options for addressing the contamination dissolved in the groundwater in the future.

He did not provide a timeline, saying, “I can’t estimate that right now.”

“General timeline,” I asked. “Two years? Ten years?”

“The groundwater process—takes some time.” Sahba said. “I don’t have a number. But, you know, it takes some time to clean up groundwater.”

The Phillips Petroleum Company (now Phillips 66) refinery in Kansas City, Kansas, pumped and treated groundwater for decades after its closure in 1982.

During permitting for the original Zink Dam in the late ‘70s, River Parks Authority planned to dump and refill Zink Lake when pollutants exceeded water quality standards.

Jerry Lasker, who headed the regional planning agency INCOG until 2007 and died in 2009, pushed back on this approach. In a letter dated Aug. 28, 1978, Lasker wrote that dumping the polluted impoundment would only push Tulsa’s problem downstream.

This statement "“Typically in engineering, the safety factor is honestly one-and-a-half or two times that,” Sahba said" bothered me. The reason there are safety factors are because things go wrong that you can't account for (fatigue, corrosion, manufacturing defects, etc). The point is that you end up building something that can withstand 200 but you only rate it for 100 because of those unknown factors; you don;t get to retroactively say "it's good for 200 because of factors of safety".

This groundwater pollutant and recreational space issue, to me, ends up being a bigger issue than the flood plain discussion in earlier posts. Combine the two, though, and the potential for mass contamination of downstream residential property. This is a big deal, Molly.

Was walking along the west bank by the old kayak ramp on levee C and saw pools of oily sheen and small springs of ground water coming from the banks and feeding the pools along the bank. Took a few phone photos.

Not sure of any caps south of the dam around the power plant.